____________________

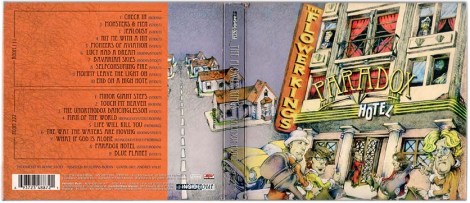

Paradox Hotel

Released in 2006, Paradox Hotel was TFK’s 9th studio release and their 4th double LP. As such, it garnered initial criticism from voices within the progressive rock community, largely questioning the ability of the band to back up with strong writing what could be perceived as excessive self-gratification. And perhaps some of TFK’s more concise, single-disk releases had greater cohesion, simply due to shorter running time, but Paradox Hotel has particularly resonated with me as one of the band’s greatest pieces of writing – all 127 minutes of it. While it doesn’t have a singular epic structure as does 1999’s Flower Power, nor the hugely anthemic qualities of “Stardust We Are,” it does boast a strong and multilayered theme that grabbed my attention when I first came across this band ten years ago.

To be fair, that theme is one that resonates within a lot of Stolt and Fröberg’s writing. The Flower Kings are what I’d call a “big picture” band, largely concerned with big questions of life, love, and coexistence, often chasing themes of original sin, divinity, and an overarching cosmology that has a lot more in common with the 1960’s “love is all you need” mantra than it does the modern music scene of which it is a part. Some might perceive that style of writing as overtly saccharine, but the broad scope of the ideology is appropriate for the band’s symphonic sound and soaring vocals: lofty perspectives on life, the universe, and everything.

Another criticism Paradox Hotel frequently received was for its caricatured artwork. The album cover features the band with grossly exaggerated cartoon features, all with their instruments in tow outside of a San Francisco style high-rise, about to enter the front lobby. Visible in one of the upper windows is a collared and quizzical-looking priest, clutching a Bible in one hand, his eyes cast toward the sky. A bearded sailor with a pipe stands framed in another window overlooking the street; yet another window opens into a miniature view of the earth itself, seen from the lunar surface. A small village of identical, cookie-cutter houses is just around the corner from the hotel, wrapping around the album’s spine and onto the back cover. The LP’s 28-page booklet is further stylized as a guestbook from an old-fashioned bed and breakfast, with more comic representations of the band and subject matter throughout. Furthermore, the liner notes are full of inside jokes, odd misspellings, and other forms of self-deprecating humor – all of which is appropriate for an album that is attempting to put a mirror up against humanity. The implication is that the one perusing the booklet’s contents is leafing for the next available check-in time. Certainly, none of us wants to come face-to-face with our own grotesque features – our insecurities, our misshapen ideas about life – but as the band has been rendered, so must the listeners in order to comprehend the elements of this musical, allegorical overnight stay. The hotel represents a type of interstitial place: a mysterious locale where revelation, introspection, and transformation may all occur. And as such, the hotel becomes a microcosm of our very world and our temporal, transitional existence: rented space, in which we only have so much time to figure it all out.

__________________

1. Check In

Disk one is subtitled “Room 111,” and the album’s opening track is simply called “Check In.” This brief track serves as an introductory piece, featuring sound samples from the Apollo 7 mission launch and concluding with Houston’s final countdown, fading to a bouncing pingpong ball at the moment of ignition. This repetitive, indecisive and plastic sound seems indicative of the back-and-forth game played within the paradox in which we find ourselves. At this point, we as listeners have entered the hotel along with the other guests, and will inevitably find ourselves facing the lives and stories of many others on the same journey of discovery.

____________________

2. Monsters & Men

Track two, “Monsters & Men,” is the LP’s first epic and functional overture, clocking in at 21:21. The Flower Kings are notorious for this kind of top-heavy approach to their album structures – mammoth pieces of writing up front, shorter tracks following suit. This piece is told from an enlightened perspective, but one still within the framework of the hotel – one still “finding out where to go,” a “simple man like you.” Perhaps he’s the hotel’s proprietor, or maybe just its chef; regardless, he’s someone who has seen and understood, who has tried and looked and “freed the inner eye.” Part one of the composition, “Seasons of War,” moves in a strong march tempo, taking the explorative themes of the opening launch sequence and giving the mission a trajectory not into outer space, but into the hearts of fellow men – an exploration into the human soul. The second movement is a piano ballad, subtitled “Prophets and Preachers,” and begins after an extended recap of the tune’s musical themes. The key refrain here is certainly an anthem of the American spirit, if not humanity as a whole: “Freedom for the underdog / Means more than his own life.” This crucial element of self-sacrifice and belief is perhaps the most important characteristic in delineating between the ranks of the “monsters” and those of the true “men.” Following another instrumental stretch, which beautifully incorporates and expands upon the same musical themes (and also includes one downright creepy clown laugh), the final installment begins. “Silent River’s” whimsical organ emphasizes the speaker’s disillusionment with organized religion’s enigmatic haze of purpose: “a million driven by a secret holy plan.” These, by the narrator’s estimation, are more like non-corporeal souls floating helplessly in a sovereign current than fully realized human beings. This final segment particularly highlights the continuous stretch of time and potential that binds all eras and cultures of humanity together, giving each of us the chance to climb the mountains set before us. The lattermost instrumental stretch recapitulates central themes, setting some of them in minor tonality, and gradually fades to a disjointed conclusion of ethereal keys. Now that we’ve been shown the key breakdown of the paradox, we are ready to meet some of the more specific figures.

____________________

3. Jealousy

“Jealousy,” track 3, begins with gentle piano and strings, a lush and theatrical tapestry, belying the violent intent contained within the lyrics: “How I love when you’re down / I love when your wings are nailed to the ground… / I’ve been taken and bent by the undertow [possibly a reference to the ‘Silent River’] / I hope you hurt like I hurt, I do.” Writ small, the narrator is merely a “lonely and cold jealous boy,” the type to calculate and observe the pain of others – a pain that is necessary for rendering some shade of feeling in an otherwise callous heart. They say, of course, that misery loves company – not camaraderie, but comparison. For a sociopath, cruelty is perhaps the only possible avenue to sensation. Jealousy personified – writ large – truly fits this category: as one of the cardinal sins, coveting isn’t merely wanting what someone else has. It’s the desire to plunder, to crush. As an endemic trait of humanity, Jealousy is a major “monster” in the hotel’s guestbook.

____________________

4. Hit Me With a Hit

From the dissonant conclusion of “Jealousy,” the album moves into the rapid 9/8 pace of “Hit Me With a Hit,” which likens the greedy demands of record label executives – a metaphor for the ones who hold all power in this hotel – to the unconscionable drive of human progress, which excises the heart and aesthetic from life in pursuit of utilitarian profit. The allure, of course, is the esteem and grandiosity of commercial success – the invitation to “dine with presidents” and boast a “familiar face” to the masses is hard to pass up. This five-and-a-half-minute piece is one of the more memorable compositions on Paradox Hotel for its instrumental and vocal hooks as well as the snarky caricature it paints of the powers that be. I love this piece for its grand instrumentation and for its tongue-in-cheek, 4th-wall-breaking challenge to critics who listen to albums like Paradox Hotel and say they “don’t want bloody poems” – just money-making records that scratch the popular itch. To truly characterize this hotel guest, the figure must be Greed, a close companion to Jealousy – likely propping up his feet in the same suite.

____________________

5. Pioneers of Aviation

“Pioneers of Aviation” is the album’s first instrumental track, topping seven minutes. The driving rhythmic force and steady cowbell – reminiscent of a hammer falling on an anvil – undergird some initial dissonance and Minimoog swirls, bringing the piece into a triumphant refrain. It’s easy to envision great aeronautics factories rising, giving shape to space exploration, adding fuel to mankind’s historical (Western?) quest for exploration and expansion. The tune wordlessly encapsulates a sense of the grand vision, capturing a sense of progress and motion, yet concluding ominously with droning organ: everything is not perfect, even where this particular hotel guest, Progress, is concerned. Whether ranked with “monsters” or with “men,” this figure has the potential to oscillate.

____________________

6. Lucy Had a Dream

“” seems to take The Beatles’ character of Lucy and cast her into the role of a listless dreamer, a young woman whose restless mind has been uncomfortably awoken to the bigger realities of the cosmos (probably from all the LSD). The “men just moving in and out of her life” just prove that “she’s not dead, she’s alright,” but ultimately indicate that what is missing from her life is a sense of purpose – conspicuous by its absence. She finds herself a guest in the hotel, the Seer in the guestbook (perhaps even the voice of “Monsters & Men”), whose awakening to greater realities still has much left to be realized. Here, the mocking clown laugh also recurs in an eerie, carnival-esque segment, in which Wurlitzer and guitars swirl in a slow ritard – a drug haze in the “back of a 60’s Cadillac,” or a recurring dream (or nightmare). The final instrumental passage fades to a satirical, profanity-laced radio advertisement for flying machines, and then transitions into “Bavarian Skies.”

____________________

7. Bavarian Skies

At some point on each TFK album, Roine will break out some unusual vocal effects, and that moment comes on Paradox Hotel with “Bavarian Skies.” The narrative voice here is rendered almost comically monstrous and is perhaps spiritually linked with – or might possibly be another incarnation of – Jealousy. “Bavarian Skies” seems to illustrate the evolution from callous little boy into true megalomaniac, personified as Hitler’s Nazi Germany – the entity most symbolic of all the ideology and hatred against which this record speaks. Such a portrayal is indicative of the vast extremes this record seeks to reveal: cruelty manifesting in childhood, left unchecked, can ultimately result in the waywardness of an entire political group. Perhaps this hotel guest is best called Ideology: a potential monster in the guestbook, should the perverse bedfellows of Greed and Jealousy become an overwhelming influence.

____________________

8. Self-Consuming Fire

After the instrumental conclusion of “Bavarian Skies,” “Self-Consuming Fire” enters on the pastoral plucking of nylon-stringed acoustic guitars. The central figure of this piece is once again the Seer, Lucy, “searching in the book of dreams,” “dreaming of a desert flower,” navigating her persistent loneliness and ultimately searching for a greater depth of meaning. Her role in this morality play is conflicted, because on one hand she recognizes her own potential for monstrosity: part of the rat race, she’s lived a “life amongst the living dead / Afraid to see what’s building up inside of her,” yet remains desperate to “escape the wildest fire / The fires that consumes her soul.” Such internal strife is a key motif for Paradox Hotel, as the dividing line between what constitutes “monsters” and what constitutes “men” is repeatedly explored, often in this internalized manner.

____________________

9. Mommy Leave the Light On

All human beings, no matter how old, still harbor a childlike need for security. That is the theme of “Mommy Leave the Light On,” but the sought-after peace of mind is elusive in this hotel when there are monsters staying in the room just next-door. For that reason, we will often seek to deceive ourselves into merely believing that everything is okay: “Mommy, can you tell me why / There is no way we can escape from dying? Mommy, can you tell me I get well? / I really don’t care if you’re lying.” Jesus said the Kingdom of Heaven, that place “far beyond the skies,” was only accessible to those with faith like a child; therefore, the childlike innocence of this piece is a point of entrance: in order to truly overcome death, violence, and all the other sins of mankind, what is required is this innocent expression of need. Rather than allow our fears to drive us to destructive tendencies, rather than allow the damning influences of Jealousy and Greed and others to drive us to isolation, we must rather be driven to community. I love the juxtaposition of the child Innocence in this piece with the child Jealousy: one is cold, heartless, and ultimately self-absorbed; the other speaks from a place of fragility and dependence, yet clings to hope.

____________________

10. End on a High Note

The title “End on a High Note” seems almost like band commentary on the presented material – all this heavy stuff needs something upbeat at the culmination of part one. This final piece on the album’s first disk is certainly a composition with bright and uplifting instrumentation (i.e. 12-string acoustic guitar, sleigh bells), with lyrics that paint a gorgeous picture of the sunrise and hint at man’s achievement of flight. This song describes the inherent beauty in diversity and the potential for global harmony: “I can see the beauty / In a thousand different faces … / Everybody is special / It’s the highlight of their story.” This soul-lifting revelation is rendered as a new morning dawning: the realization of unity and progress should bring peoples of all nations together in a new beginning. Rather than consistently drawing battle lines between the “monsters” and the “men,” “End on a High Note” suggests that we should eradicate such binary perceptions and draw together as human beings for the greater good. In the hotel’s guest registry, there are plenty of figures cast sharply as villains or as heroes, and despite the tendency to deem some “bad” and some “good,” each has a unique purpose to play. The bottom line? No one is irredeemable.

____________________

11. Minor Giant Steps

This brings us to disk 2 and “Room 222.” Now that we’ve been introduced to the major players (guests), we move to this latter phase – from introduction to interpretation. “Minor Giant Steps” is an easy favorite track on Paradox Hotel, simply due to its bright, melodic nature. The anthemic choruses cite Progress as a figure with his own internal paradox: sometimes the biggest movement forward comes from the smallest choices. In reference to society and to history, all major change is really bottom-to-top revolution: it takes the “minor giant souls” of individuals with the guts and the determination to affect change at any sustainable level. Thus the title, which seems to borrow from Neil Armstrong’s iconic radio transmission back to Houston during the Apollo 11 moon landing (“’69, we were walking on the moon”): it’s the small decisions and inconsequential acts, all chained together, that produce the biggest and longest-lasting change. By the same token, all it takes are “words to start a war” – minor, giant infractions. All things considered, this tune takes into account the utter fragility of mankind, but rather than taking a pessimistic tone, the narrator – likely the same voice as that of “Monsters and Men” – instead regards such porcelain qualities as cause for protecting, nurturing, and cherishing. The irony is that the masses – those outside the enlightening space of the hotel – tend to view progress only as a chance to “keep on exploiting until the end,” rather than an opportunity to search for the “new world… hiding behind the door.”

____________________

12. Touch My Heaven

Unsteady mellotron, muted percussion, and ethereal guitar swells weave a claustrophobic backdrop for “Touch My Heaven.” Subtle guitar quotes of “Lucy Had a Dream” point backward to the hazy revelations of the hotel’s resident Seer, further pressing the issue of internal strife pertaining to individual sense of purpose. An extended instrumental stretch captures the turmoil of emotion, the wordless emotional grappling. The speaker’s soliloquy, to “stay here on the floor” or to rise up and reach for hope, is an apt depiction of mankind’s persistent angst – to be controlled by circumstance, or to be the master of individual destiny. Victim or victor, this is a challenging dance to master for anyone.

____________________

13. The Unorthodox Dancinglesson

It seems appropriate to move from the internal monologue of “Touch My Heaven” to “The Unorthodox Dancinglesson,” despite the abrupt shift from dreamy instrumentation to growling pentatonic scales. This instrumental piece is aptly titled, because setting choreography to such an erratic meter would be an extraordinary undertaking. The dancing lesson is a metaphor for identifying “how we play a part / In the tireless games” (“Minor Giant Steps”), for partnering strange and paradoxical elements of life into an awkward and unpredictable two-step. The conclusion appropriately devolves into cacophonous riffing, returns to the central theme, and ends as abruptly as it began.

____________________

14. Man of the World

“Man of the World” paints a picture of mankind’s constant, restless motion – the search for companionship, contentment, and rest. This piece echoes the sentiment of “Self-Consuming Fire,” albeit from a less enlightened perspective. The speaker here – perhaps Everyman, or maybe a more specific business executive type figure caught in the rat race – trades the “world for the blue sky,” but rather than moving toward a specified heaven, he notes that he is moving away from a sense of home and belonging, as opposed to finding them. Despite the upbeat and bright feel of the composition, the lyrics betray the facade of optimism that seems to plague so many human beings: “One day,” we say, “We’ll figure out this disillusionment. One day, we’ll understand why we aren’t happy, and we’ll know how to fix it.”

____________________

15. Life Will Kill You

The conclusion of “Man of the World” fades directly into the alternating meter of “Life Will Kill You.” Together, these companion pieces illustrate the intuitive regrets of self-based living, of working bodies to the bone for the sake of profit and false security. This is the accused sentiment of “Hit Me With a Hit” – the drive for prosperity at the expense of beauty, life, and joy – and feeling trapped as a result. Semi-audible radio transmissions filter through the guitars like a distant reminder that there is more to life than what keeps our spines curled over our desks, but the ultimate conclusion of this piece is that – in the end – it’s all the living that brings about our deaths, or rather that which we mistakenly perceive to be “living”: the 9-5 shift, the yearly electronic upgrades, the self-absorbed pursuits. This undermines all the entitled victimhood that persists in our world, because all of this is “nobody’s fault but mine.”

____________________

16. The Way The Waters Are Moving

In “The Way The Waters Are Moving,” the speaker again identifies the passing of time (“Summer is gone” / “I’m growing older”) and evaluates that something fateful is pushing events on earth toward an inevitable conclusion. This piece is dedicated to “tsunami victims and survivors,” specifically those impacted by the undersea earthquake and resulting tsunami in the Indian Ocean at the close of 2004. On one hand, the undercurrent of destiny in this piece raises questions about man’s finite uncertainty and tortured existence: “I’ve asked myself a million times / Why I have to lose and suffer.” It takes into account that the waters don’t always move in the same way, sometimes sweeping away some in an instant while leaving others to drift, “slowly dying” instead. Remember also the implication of “Silent River” back in “Monsters & Men,” which likened moving waters to the oppressive current of religion. Stormy doctrinal seas akin to James 1, rather than the Eden-esque “still waters” of Psalm 23, can contribute to spiritual catastrophe with a death toll as crushing as that of a natural disaster, motivating racial, cultural, and personal conflict for the sake of ideology.

____________________

17. What If God Is Alone?

The role of fate in tragedy appropriately sets the stage for “What If God Is Alone?”. This piece opens with the distant sounds of crowd noise, representative of the human masses on planet earth, rising within the gentle percussion and ethereal guitars of the intro. This piece hints back to previous lyrical ideas of traveling beyond the world into the stars: “sailing across the Milky Way”; “’69, we’re walking on the moon / Sending those waves to see if we’re alone”; “I traded the world for the blue skies.” The lyrics suggest the age-old mythology of man being on a quest to reach his maker, driving to the stars and beyond “time / words / suns / worlds” to achieve heaven, to be godlike in transcendence, and to leave behind all of our “greed and hate and pettiness.” However, the lyrics go on to equalize what is divine and what is earthly: they render God less a Judeo-Christian omnipotent creator than a sub-deity more akin to those within the Greek Pantheon — a victim himself and desperate human contact — and man as a being capable of growing beyond his limitations merely by fixating on what he perceives as God. And if, as the lyrics suggest, the entity we refer to as God is absent from our raging seas, leaving us “in the dark [where] there is no light,” then perhaps it is incumbent on mankind to assume His role.

____________________

18. Paradox Hotel

With that frame of reference in place, the album’s title track works as the moment of stark revelation: suddenly, the mask is off, the curtain comes down, and the earth is cast in stark tones and grotesque images: a “house [that’s] nothing but a roundabout” (nod to Yes), a cyclical purgatory – or, worse yet – a “living hell” populated by “bankers, lawyers, and politicians.” This grossly accusatory piece attacks the ideology of “life in the fast lane” (nod to The Eagles), thriving on knowledge, power, and getting high on the obscenities of others (i.e. “Jealousy,” “Hit Me With a Hit,” “Bavarian Skies”). Pulling no punches, this piece drives home with ardor the harsh reality that existence is fraught with people stuck in the old binary way of thinking and living (“Some people are good, some people are bad / But we seem to remember all the fun we’ve had”) that only leads to warfare and bloodshed. As the glaring refrain fades, the final sounds are part of a radio transmission back to Houston: “Now we’re switching so we can show you the moon.” With this moment of observation, we as listeners finally seize upon the exhortation of the narrator way back in “Monsters & Men” to leave this “place we call home” in order to get a rocket’s-eye view of our cosmic neighborhood and understand ourselves more clearly.

____________________

19. Blue Planet

The final composition, “Blue Planet,” is the moment of stepping foot outside of the world and ourselves, looking down on the “innocent blue sky” now below our feet, a dome that encapsulates not just the gross state of human affairs, but also its incredible potential. From this godlike perspective, everything becomes so clear, and we begin to wish that “everyone could see and feel the way [we] feel.” The lyrics here quote “Monsters & Men”: if only we could break the paradox, awaken mankind to reality, and collectively seize upon our potential, then “there’s a mountain we could climb.” Yet despite the incredible height to which the narrative has ascended, the album’s conclusion is instead cynical: “You’re stuck with us [liner notes – Roine says “between Flower Kings” on the recording] and your dreams / Inside revolving (hotel) doors.” The final moments of the album are one last excerpt from an Apollo 8 transmission back to earth, describing in great detail the intrinsic beauty of the little blue planet in quiet rotation, much of its ambitious face obscured by cloud. While words in and of themselves are powerful and eye-opening, we were recently told that they also have the potential to “start a war.” Therefore, despite the revelations of a few, something more than mere enlightenment is required to “break the lousy chain of inherited habit… imperiling [us] all” (Catch-22) in order to truly break free and check out of Paradox Hotel.

____________________

Spotlight Conclusion

To me, the question remains, what exactly is the paradox of this hotel we call earth? Is it the contrasting ideals of mankind, which are often incompatible? Is it merely the juxtaposition of opposites? Is it the contrast of valuing the individual seeking to “free the inner mind” weighted against the vast scale of cosmic significance? It could be the cohabitation of the hotel by both Monsters and Men – heroes and villains, spiritual leaders and spiritual oppressors, those who are capable of compassion and those who aren’t. If we’re truly honest with ourselves, rather than seeing all of humanity in such binary light (a concept this album really seeks to challenge), we’d be willing to recognize that much of the paradox exists within our own hearts: in so many ways, we are each torn between our desire to love and be loved and our own closet demons — the selfishness that somehow coexists with all of our good intentions to be selfless. Furthermore, in evaluating the key figures filling the guestbook, it becomes more and more apparent that even the monsters we can’t truly live without: jealousy is intrinsic to love, just as greed is intrinsic to progress. Capturing and transforming all elements of human emotion and experience is in itself a paradox of existence, combining the yin and the yang, harnessing the id and the ego in order to right what is wrong and advance toward what is ultimately to be desired.

To take one further step backward, Paradox Hotel itself is paradoxical for its simultaneously critical yet optimistic view of humanity. It’s inspiring because it sees the potential for human greatness despite all the wrong that has persisted throughout history. It takes into account that there is something broken about us, and yet posits that there is a way forward to the healing of the “sacred heart” of mankind. These broad brushstrokes are a good foundation for those who stand for social justice, for preserving our world, for encouraging love over hatred. The challenge of implementing change, of course, is in the details – in the inspiration of individuals and nations to take their part.

Paradox Hotel, therefore, works within the framework of viewing the earth, and human existence itself, as a permanent yet temporary state – life being an overnight stay in a rented room that other generations will inhabit after we’re long gone. Bookended by tracks that focus on taking a step outside of the world we live in, the album points to the fact that the only way to view our rented space properly is to appreciate it on both an individual and a cosmic level. The world is, in fact, a place we pay to visit (with our very lives), but it isn’t really a permanent residence, and so it should be our responsibility to do our part to preserve and prepare it for future generations. That begins with the internal “Minor Giant Steps” and spreads outward into our spheres of influence and beyond.

____________________

CD 1 (64:50)

CD 1 (64:50)

– Room 111 –

1. Check In (1:37)

2. Monsters & Men (21:21)

3. Jealousy (3:22)

4. Hit Me With A Hit (5:32)

5. Pioneers Of Aviation (7:49)

6. Lucy Had A Dream (5:28)

7. Bavarian Skies (6:34)

8. Self-Consuming Fire (5:49)

9. Mommy Leave The Light On (4:38)

10. End On A High Note (10:43)

CD 2 (62:04)

– Room 222 –

11. Minor Giant Steps (12:12)

12. Touch My Heaven (6:08)

13. The Unorthodox Dancinglesson (5:24)

14. Man Of The World (5:55)

15. Life Will Kill You (7:03)

16. The Way The Waters Are Moving (3:12)

17. What If God Is Alone? (6:58)

18. Paradox Hotel (6:29)

19. Blue Planet (9:42)

Total Time: 126:54

____________________

Brilliant analysis! It leaves me speechless and pondering deep thoughts. It’s clear this album had a vision and some interconnections but I had not realized to such an extent, though I still doubt it was all planned, it’s more probable it all just came naturally to Roine (and co). At first I had trouble getting into this one but it’s been clicking with me more and more and now that I’ve read this I’m sure I’ll grow to like it even more! This is my first time discovering this site and what you did here is something that should be done more often in my opinion when talking about progressive music as it’s often done with such honesty by musicians not afraid of revealing their deep thoughts… Really, great job!! This is inspiring.

LikeLike